Fear acclimation via height exposure – a practical application

*

So far in this fear management journey via height exposure, we have seen a series of theoretical key points. Just in case you are joining just now, let me summarize them very briefly:

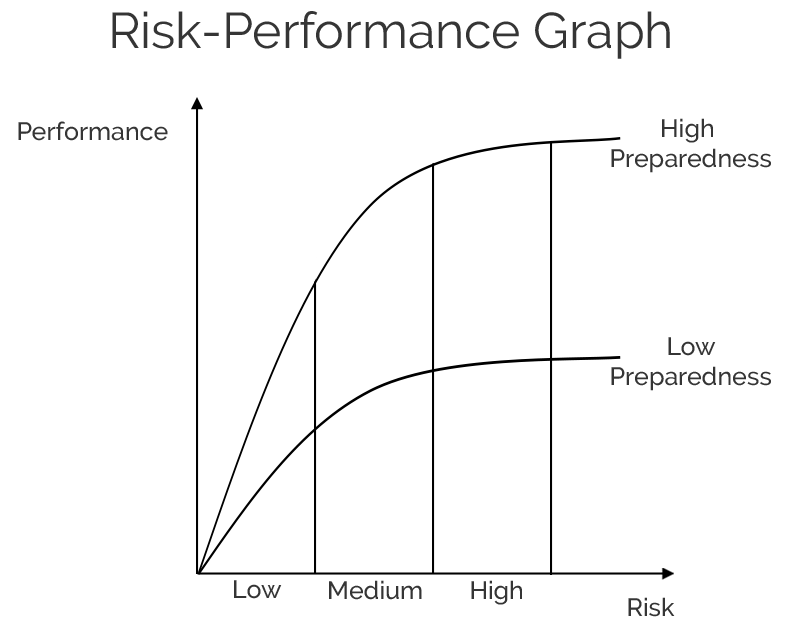

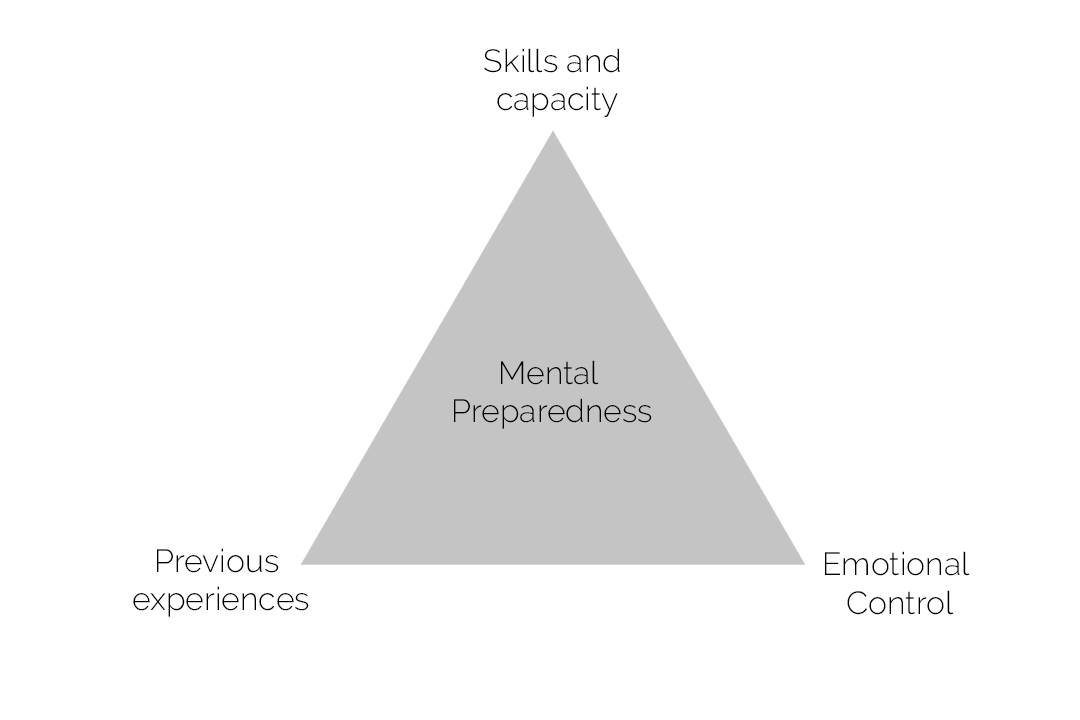

- Fear is an automatic mechanism, it is a friend and a companion that can help us discriminating dangerous situations from those that are safe. Even though we cannot change the effects fear has on our bodies, our preparedness levels can increase our ability to confront it.

Click here for the “introduction to fear management” article

- When we consider Fear exposure and preparedness, there is only a limited number of situation that can allow growth. Below or over that stage, there is either comfort or danger and nothing relevant can be learned from it. Therefore, you have to learn how to pick the right scenario for development.

Click here to read about the “fear preparedness matrix”

3. For a given risk, only one performance outcome is possible, and that is related to the individual level of preparedness in that specific circumstance. The idea that everybody can do anything without adjusting risk to preparedness is just an illusion.

Click here to find out what the “risk illusion” is

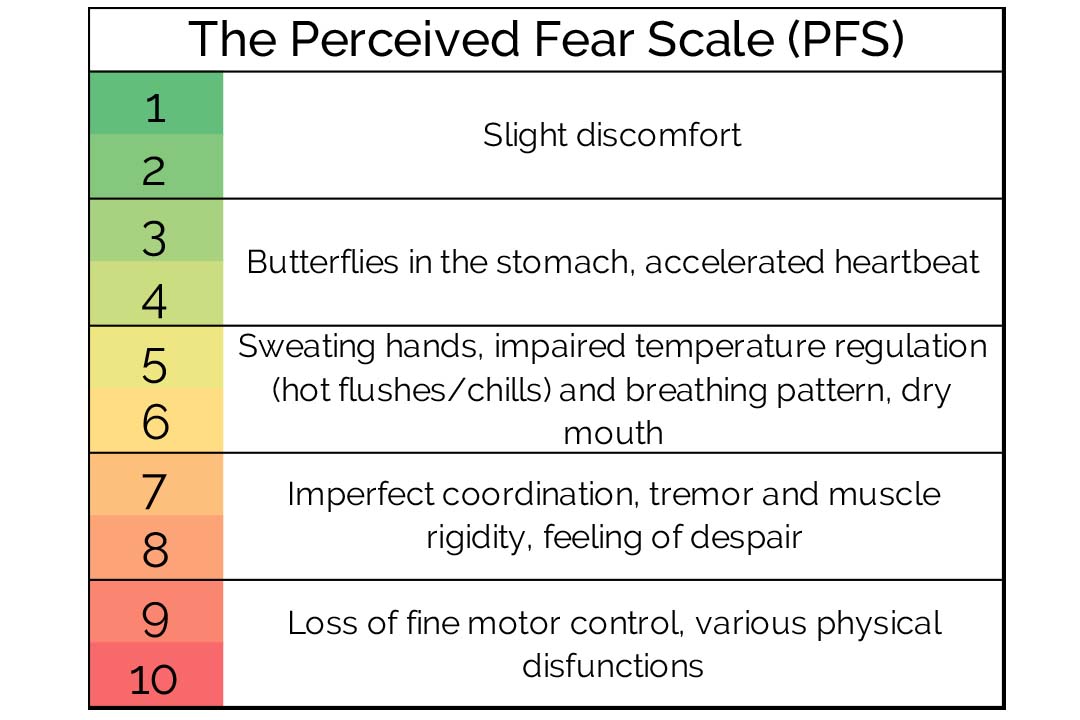

- Humans’ perceptions and instincts are inner signals that can and should be trusted (once tuned). I have developed a scale to identify the severity of fear’s symptoms called the “Perceived Fear Scale” (PFS). Know the scale, know yourself, leave little to nothing to chance.

Click here for check the perceived fear scale

Make sure those points are as clear as the sun before moving on. If not, go back into the articles; read them thoroughly and let the understanding sink in.

Now, a question will be pending out of your tongue: in practice, how can I identify and scale those situations to the right level? If you manage to do that and go through the right process of development everything can become possible.

So, let’s start:

Picture by Arianna Barbin, in a photoshoot for Skochypstiks

I consider height exposure no different than an immersion underwater (freediving). You need to learn how to get comfortable with being in the water first; learning how to manage your resources: oxygen levels, time, energy, surroundings and emotions, to name a few.

From there, you can swim around and progress to different stages or layers of immersions: 3-5-10-15 meters and so on…

After many hours spent practicing and only once you are ready, you can perform proper tasks. I.e. Exploring an underwater shipwreck.

However, if you get to that level, everything else will certainly be covered and you will be able to make the practice of water immersion yours.

This metaphor remains when thinking about the necessity of a gradual state of exposure. If you dive deep too fast or too soon, it won’t work. Your air won’t last, you would be wasting energy, you would not handle the stress. An “acclimation” phase is necessary for sustainable development.

Following from here, the basic stages on a first phase that I have isolated on a fear exposure are three:

– Static progressions

– Dynamic progressions

– Task orientation

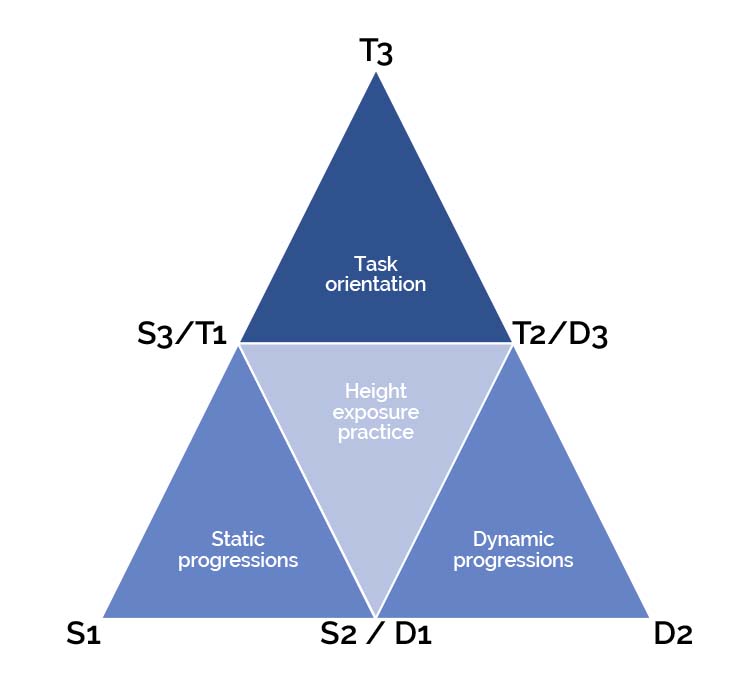

In the diagram, you can see the progressions for any situation a person could possibly encounter during the height acclimation journey. Once adjusted by the level of preparedness, each stage can provide enough exposure to trigger a positive adaptation.

The figure is composed of three different pyramids combined; one of the static progressions, one of the dynamic progressions, the task orientation one.

The static pyramid < the dynamic pyramid < the task orientation pyramid.

At each corner, you can see the three stages, based on the typology of the drill; 1,2,3. It is progressive starting from the lower left corner and from there in a counterclockwise direction.

I.e. S1 Interestingly, S2 appears in combination with D1. S3 with T1. T2 with D3. Therefore, the whole progression appears to be slightly scattered. It doesn’t appear to be just linear S1-> S2 -> S3 -> D1 -> D2 -> D3 -> T1 -> T2 -> T3. It can be more variable: S1-> S2 -> D1 -> D2 -> S3 -> T1 -> D3 -> T2 -> T3. This highlights complexity and fluctuation in progression. I.e. standing on a wide surface with no protections around. Lean forward – lean backward, exploring the boundaries of balance. Spend time in stillness until all symptoms of vertigo diminish. Find a higher place, repeat. I.e. hanging on a high wall with a little buffer to failure, performing some static positions on a rail without moving at height etc. i.e. passing a ball at height with a partner, catching and throwing without moving, scanning for options.

- Dynamic 1 (D1): Dynamic Comfortable

i.e. walking on a wide wall at height, back and forth, turning 360 degrees, doing small jumps on the spot, etc.

- Dynamic 2 (D2): Dynamic Uncomfortable

i.e. locomoting on a rail at height, performing a traverse on a high wall.

- Dynamic 3 (D3): Dynamic Drill-Based Exercise.

I.e. Walking forward on an edge at height with a partner. The two people should be connected by a stick from the belly of the first one to the back of the second one. The stick should not fall.

- Task Orientation 1:

i.e. walking the perimeters of a building in a circle.

(The task to perform should be easy, manageable, replicable at ground level)

- Task Orientation 2:

i.e. Climbing a bridge perpendicularly in the middle with water or the void underneath. The task can also be completed safely on the side as a preparation first.

(The task can be performed on the side).

- Task Orientation 3:

i.e. performing a jump at

(It should not be possible to try the task beforehand, there is no way back once you are in the middle of it).

Make sure you don’t skip the stages for acclimation, nor you regress too much. Be brave, be true, be smart.

Until next time,

Marcello.

Recent Comments