The Fear-Preparedness Matrix

As previously underlined, there is not much that can be done to “avoid” triggering the neural circuits associated with fear, nor it is safe or wise not to listen to its call.

Fear makes our senses sharper and our bodies more ready to face the unknown.

Balancing on the high beams with ParkourWave – Bergamo, 26/04/2018. Pic by Andy Day – All rights reserved.

A lot of complicated words to say that the fear-response system becomes more useless than a cockroach floating upside down in a pool.

So, being able to control and channel the responses of the body is essential. A good process into this world can open possibilities to various activities that will ultimately lead to the development of a stronger mind and a more adaptive body. But how can we be sure we are not stepping over the line and we are working in the right area for our development?

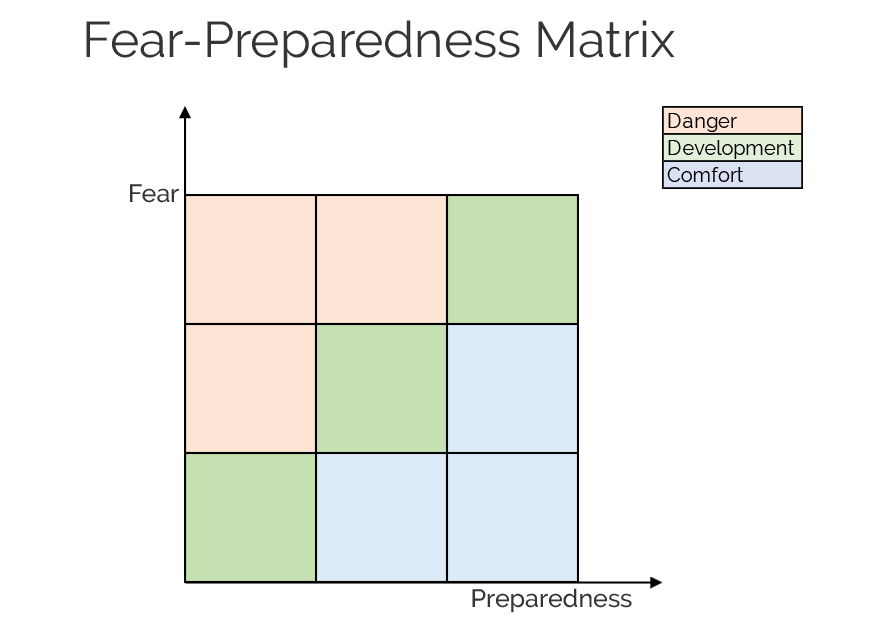

Here is a matrix that can be of help in understanding where to spend energies and time to produce positive adaptations:

The matrix underlines that, for a given stage of fear exposure and preparedness state, there is only a limited amount of situations that can allow growth.

If the preparedness of a person is very low, the fear to which that person can be exposed must be low; failing to do so can produce an impaired state, at times creating long-term damages on the body or augmenting the so-called fear of fear.

I.e. Amber is learning how to balance on a rail. Practicing ground level would be necessary to ensure her development. If the whole process started on a high bridge, nothing good could have come out of that situation, in the first place. She would have probably frozen at that height before slowly climbing down the bridge – in a moment she would have associated rail balancing to a bad experience precluding to herself a whole branch of personal development.

As the preparedness gets “bigger” in value the fear exposure can go hand in hand with it. On the other hand, a new riddle arises. With more tools to face the problems, comes the risk to sit in the comfort zone, producing no more adaptations in the system.

I.e. Luke is an experienced fighter – lightly sparring over and over again without ever going into a real fight will leave him both without a reality check and without an understanding of the deepest layers of his practice.

For today, that is all. Remember – Don’t be crazy but don’t be lazy. Start from manageable, controlled and expected situations not to drown in a sea of chaos. With time move into harder and unexpectable scenarios where you level of skills can be tested and progressed.

In the next article, I will present the basic elements of which this “preparedness” I have been talking about is comprised of and I will discuss the two main methodologies that I have been implementing during the years for the development of my students.

Until next week,

Marcello.

(1) LeDoux, J. (1994). The amygdala: contributions to fear and stress. Seminars In Neuroscience, 6(4), 231-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/smns.1994.1030

Recent Comments